The Macbeth has been a music and arts pub for over 100 years. Offering great entertainment not to mention good food and drink. Our intention has always been to continue this tradition, So not that much has changed apart for the costumes and music styles over ever since Charles Dickens used to prop up the bar.

This pub has survived two World wars, Typhoid and an unrelenting bombardment of some of the best intimate live performances and parties known in the western hemisphere.

It has also – so far – survived Hackney Council’s continuing mission, to sterilise culture and diversity in this historically colourful borough.

Long may it continue…

Fake Blood

Dan Deacon

Gallows

Pete Doherty

Roots Manuva

Dan le Sac and Scrubius PIP

Plan B

Damien Marley

David Rodigan

Eliza Dolittle

Emmy The Great

Kap Bambino

Bo Ningen

The Invisible

Bombay Bicycle Club

Metronomy

Until the Great Fire of 1666, the dirt and squalor of medieval London were still largely concentrated within the boundaries set by its ancient walls. Access to The City was via seven landward gates, ranging from Ludgate in the west to Aldgate in the east. Hoxton was in the parish of Shoreditch. It lay outside the walls, a mile or so northeast of Bishopsgate. Being close to the City and on a main route for travellers, Hoxton has been an area for entertainment, leisure and refreshment for many centuries.

The name “Hoxton” – sometimes also known in history as ‘Hogsdon’ – comes from the Saxon word Hochestone, meaning a farm or fortified

enclosure belonging to Hoch or Hocg. Way back in 1415, the Lord Mayor of London “caused the wall of the city to be broken towards Moorfields, and built the postern called Moorgate, for the ease of the citizens to walk that way upon causeways towards Islington and Hoxton”. Hoxton’s inhabitants responded by enclosing the fields and harassing walkers from the City and archers practicing their skills on Hoxton Fields. In 1514 an uproar led to the hedges and ditches being destroyed so that Londoners could enjoy the drained farmland of Hoxton. In the late sixteenth century there were “enclosures for gardens, wherein are built many fair summer houses, some of them like midsummer pageants, with towers, turrets and chimney tops, not so much use or profit, as for show and pleasure”.

The plump burghers of London maintained their gates until the 1760s and still closed them at night. Beyond the walls life continued to be less regulated and in some ways more precarious. Areas outside the jurisdiction of the City could offer bawdy inns, bordellos, gambling and dodgy entertainments such as bull and bear baiting. In those days, of course, “alternative lifestyles” frequently also involved religious dissent and for centuries Hoxton provided useful hideouts for contrarians from both ends of the spectrum – recusant Roman Catholics and non-conformist Protestant sects alike.

During Tudor times Hoxton still retained large expanses of fields and trees, making it popular with the gentry, ambassadors and wealthy immigrants looking for a better quality of life. Rich and poor still lived in close proximity and by 1601 there were over twenty houses along Hoxton Street, even though Queen Elizabeth I had banned new buildings within three miles of the city.

Hoxton also proved popular with actors, including William Shakespeare, who lived nearby. The two first purpose-built theatres in Great Britain were in Curtain Road, with a young Shakespeare writing for and acting in both. One of these theatres, simply called ‘The Theatre’, was home to at least three Shakespearean premieres, including the first ever performance of Romeo and Juliet in 1597.On 22nd September 1598 the playwright Ben Jonson (Shakespeare’s main creative rival) killed actor Gabriel Spenser in a duel fought in the courtyard behind a local inn. The location where this happened is now in Pitfield Street, N1. Jonson escaped being hanged for manslaughter by pleading ‘Benefit of clergy’. He demonstrated his ‘clerical status’ simply by reading a verse from the Bible and his sentence (for a first offence) was then reduced to branding (on his left thumb) and a brief term of imprisonment. The life-saving verse came from Psalm 51 – The Miserere: “Oh God, have mercy upon me…” Not surprisingly, it was known to London’s underworld as ‘the neck verse’.

Another notorious Hoxton alehouse was “The Pimlico”. Part of a poem of 1609 called ‘Tis a Mad World at Hogsdon’ includes the lines;

“Doctors, Proctors, Clerks, Attornies,

To Pimlico make sweaty journies”.

The Gunpowder Plot – a Catholic conspiracy to blow up the Houses of Parliament on 5th November 1605 – was discovered in Hoxton Street. It was here on the 12 October 1605 that Lord Monteagle claimed to have received the letter unmasking the plot, which led to the capture of the plotters, including Guido Fawkes. This is commemorated by a brown plaque on the wall of a modern block of flats. (The address of the flats is 244-278 Crondall Street but the plaque is on the Hoxton Street elevation.)

By the end of the 17th Century the wealthy estates in Hoxton were being broken up, with many of the large houses being used as mad houses and almshouses for the elderly or infirm. By then, the fields too had long ago been enclosed or built-over. Any remaining open spaces had become private or public pleasure gardens.

Hoxton House on Hoxton Street was turned into a lunatic asylum in 1695, becoming the biggest in Hoxton before closing in 1902. By the early 18th Century, nearly all of London’s private lunatics were accommodated in Hoxton. The name Hoxton became synonymous with lunacy and for nearly three hundred years it gained an unwanted notoriety from its private madhouses. Coleridge, in 1803, referred to Hoxton House as ‘The Hoxton Madhouse’. It included asylum departments for private (fee-paying) men and women, for male and female pauper lunatics (particularly from the City of London), and for “maniacs” from the navy. It remained the naval lunatic asylum until 1818. It also received criminal lunatics. According to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, when the Lunacy Office found a person lunatic by inquisition he became subject to jurisdiction in lunacy, and remained so until his recovery or his death.

During the early Victorian era, wealthier Hoxton residents were driven away to the new ‘suburbs’, leaving Hoxton as a poor area full of dirty, noisy slums. Workshops turned out all manner of goods, from furniture to shoes. Between 1831 and1851 the population of Shoreditch doubled, making the area around Hoxton one of the most densely populated in Europe. But it was still a focal point for actors and entertainment. The famous 3,000 seat capacity Britannia Theatre was located at 115-117 Hoxton Street from 1841-1900. The site, now occupied by a block of flats, was almost directly opposite The Macbeth. Hackney Council have placed a commemorative plaque on the wall of the Arden Estate, (103 Hoxton Street) which reads: “On this site stood THE BRITANNIA SALOON. Opened 1841. Rebuilt 1858 and renamed THE BRITANNIA THEATRE. Demolished in 1941.”

Built on the edge of the former Pimlico tea gardens, The Britannia in its pomp offered a huge auditorium with a proscenium-arch stage, stalls, two circles and an orchestra pit. The all-time record attendance was reported to be 4,790. Entry was cheap, food and drink were served inside, and three or four plays were performed every night with variety acts in between. Charles Dickens regularly visited the theatre and even compared it to La Scala in Milan in his 1865 novel The Uncommercial Traveller. Dickens sought inspiration in the streets around Hoxton. He had Mr. Micawber living at Windsor Terrace, City Road (now demolished) and he placed Oliver Twist in South Shoreditch. The Britannia Theatre was damaged by fire in 1900, became a Gaumont cinema in 1930, and was finally destroyed during the Blitz of 1940/41.

Another building unfortunately seriously damaged during World War II was Pollock’s Toy Theatre Shop at number 73 Hoxton Street. Founded by John Redington in 1851 and run by the Pollock family, it sold traditionally printed children’s card theatres. The novelist Robert Louis Stevenson was one of its regular customers.

The Macbeth has an interesting and chequered past. Like so much of our wonderfully eclectic London heritage, it began life under a different name, further down the street and on the other side. Originally known as The White Hart public house it existed from at least 1842 until 1856 at 35 Hoxton Street. Meanwhile, sometime between 1838 and 1872, The Hoxton Distillery built a fine brick and stucco public house along the road at No. 70 Hoxton Street. According to The Hackney Society – who should know – this was first intended as a gin distillery using water from an underground spring. By 1877, the London Post Office Directory was listing 70 Hoxton Street as the ‘The White Hart’ with one George Churchman as the licensee. Whether or not gin continued to be distilled on the premises we may never know but this was a grand pub and conveniently located for the actors and theatre-goers thronging to the Britannia Theatre just opposite.

The front of The Macbeth is a good example of well-mannered nineteenth century neo-classical architecture. The pilasters and fenestration on the ground floor were remodelled in the late 1940s (probably to repair bomb-damage) and have lost their original proportions along with their fluted pilasters – complete with Corinthian capitals – and a proper entablature framed by a cornice above and decorative brackets at each end. Despite this post-war disaster, however, many of the original external features remain. A true ‘piano nobile’ is still suggested by the elegant first floor windows dressed with triangular pediments and a string course to separate them from the less-ornate second floor above. The whole façade is edged with expressive quoins and surmounted by a triangular pediment in the centre of a parapet with posts and decorative vases. If you care to look up, there – in the centre of the front elevation – you can still see the letters ‘HOXTON DISTILLERY.’ moulded into the stucco.

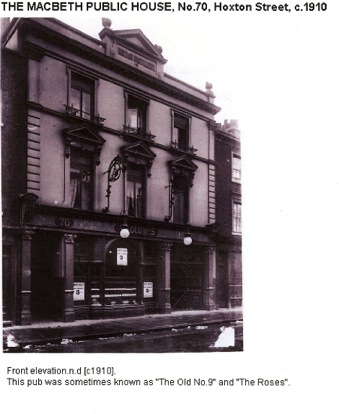

A photograph of circa 1910 shows 70 Hoxton Street with its original frontage and the title ‘The Old No. 9’ in gold lettering on the frieze above the elaborate ground floor windows. Officially, it remained The White Hart until 1978 when it was renamed The Macbeth. Where that ‘Old No. 9’ came from – or its other rumoured name ‘The Roses’ – we have yet to discover. Theories abound. Could it be that ‘Old No. 9’ commemorated a train wreck in the USA sometime in the early 1900s? (Cue Jim Reeves). Or maybe it came from a coalmine near Lansford, Pennsylvania? A favourite hypothesis – just for its patent absurdity – attributes the name to an abandoned railway tunnel near San Antonio, Texas, which is now a seasonal refuge for several million Mexican free-tailed bats. If only Jack Daniels had marketed his whisky as Old No 9 rather than Old No 7……then we’d all know where to place our bets.

The choice of the new name in 1978 was almost certainly inspired by the strange mural along the side wall of the saloon bar. Hand painted on glazed ceramic tiles this depicts the banquet scene from Shakespeare’s tragedy, Macbeth, [Act III, Scene 4]. This is the sequence in the play where Macbeth is haunted by the ghost of his former comrade-in-arms, Banquo, whom he has just had murdered. The dramatic impact is enhanced by the fact that only Macbeth can see the ghost (“Thou canst not say I did it. Never shake Thy gory locks at me…”) and everyone else gathered around the table suspects that their new king has finally gone off his rocker.

The mural is the work of W.B. Simpson & Sons, established 1833, who are happily still active in the specialist tile business. Their murals were very popular in London pubs and hotels throughout the latter years of the nineteenth century and the Macbeth mural probably dates from the 1880s, if not earlier. It remains a slightly odd choice for a pub interior…Macbeth and his missus having a domestic in front of all their friends and neighbours…and a ghostly presence spoiling the feast. (HE: “Hence horrible shadow! Unreal mockery, hence!” SHE: “You have displaced the mirth, broke the good meeting with most admired disorder.”) It becomes even stranger when you consider the proximity of this watering hole to the Britannia Theatre and remember the superstition that actors traditionally have about how ‘The Scottish Play’ can bring bad luck to a theatre after only the merest whisper of its name…

By the 1980s a new generation of young artists – looking for cheap workspace – started to move in. Pubs and clubs opened around Hoxton Square to cater for the creative crowd, bringing with it a vibrant arts community, new money and regeneration. Hoxton Street, however, still retains the feel of a traditional, close-knit London community – and one with a pretty amazing past and present. The Macbeth itself wasn’t at all famous until Amy Winehouse’s boyfriend nearly killed the previous landlord and thereby created a massive scandal. Avid readers of the tabloids ( apart from those directly involved ) thought this was ‘cool’ and the venue gained a temporary notoriety – much to the delight of the new operators who benefitted from all the free publicity which helped get the pub up and running without them having to pay huge P.R fees…

Cheers for that!

If you have any enquiries about live musical acts please don’t hesitate to contact us on: themacbethlivemusic@gmail.com